Innate vs. Adaptive Immunity: Understanding the Body’s Two-Tiered Defense System

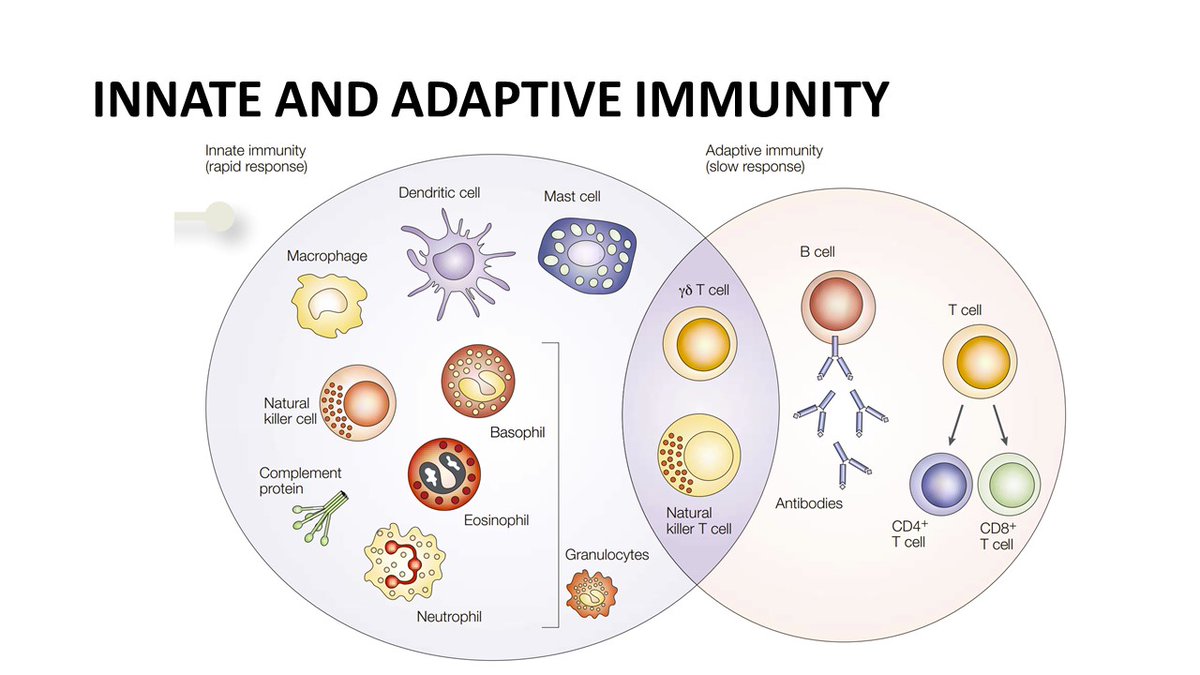

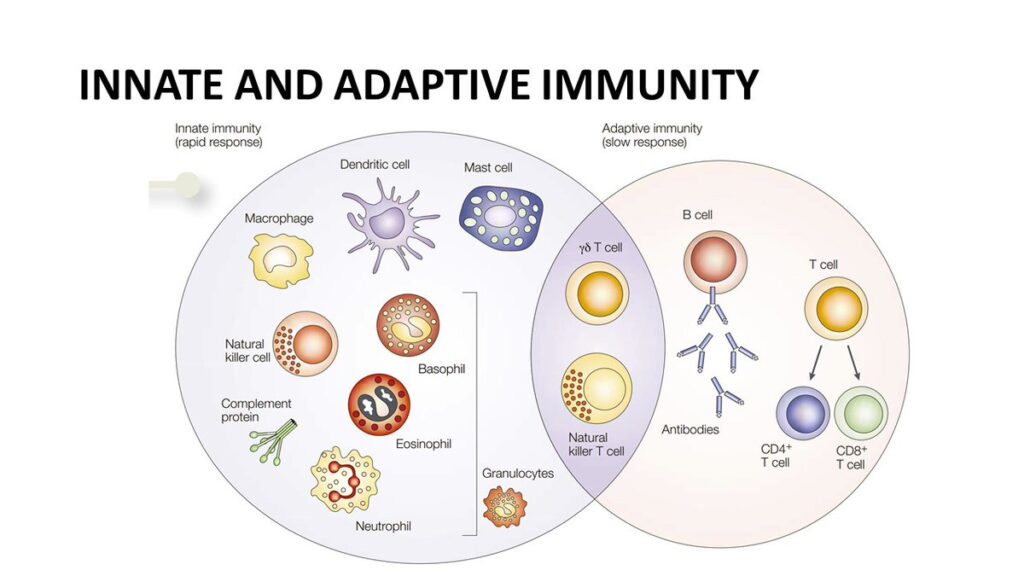

Our bodies are constantly under attack from a barrage of pathogens, from viruses and bacteria to fungi and parasites. To combat these threats, we rely on a sophisticated immune system, a complex network of cells, tissues, and organs working in concert to defend us. This immune system is not a monolithic entity; it’s more accurately described as a two-tiered defense system comprised of innate and adaptive immunity. Understanding the differences and interplay between innate adaptive immunity is crucial to grasping how our bodies protect us from disease.

This article will delve into the intricacies of both innate and adaptive immunity, exploring their mechanisms, components, and significance in maintaining overall health. We will examine how these two branches of the immune system collaborate to provide robust and lasting protection against a wide range of threats. The efficiency of innate adaptive immunity is what keeps us healthy.

What is Innate Immunity?

Innate immunity is the body’s first line of defense, providing immediate, non-specific protection against a wide range of pathogens. Think of it as the security guard at the front door, ready to respond to any potential threat without needing prior experience. This system is present from birth and doesn’t require prior exposure to a pathogen to be activated.

Components of Innate Immunity

- Physical Barriers: These include the skin, mucous membranes, and the linings of the respiratory and digestive tracts. These barriers physically prevent pathogens from entering the body.

- Chemical Barriers: These include substances like saliva, tears, and stomach acid, which contain enzymes and chemicals that kill or inhibit the growth of pathogens.

- Cellular Defenses: Several types of immune cells contribute to innate immunity:

- Natural Killer (NK) Cells: These cells identify and destroy infected or cancerous cells.

- Macrophages: These cells engulf and digest pathogens and cellular debris through a process called phagocytosis.

- Neutrophils: The most abundant type of white blood cell, neutrophils are phagocytic cells that are rapidly recruited to sites of infection.

- Dendritic Cells: These cells act as messengers between the innate and adaptive immune systems, presenting antigens to T cells to initiate an adaptive immune response.

- Mast Cells: These cells release histamine and other inflammatory mediators, contributing to the inflammatory response.

- The Complement System: This is a cascade of proteins that enhances the ability of antibodies and phagocytic cells to clear microbes and damaged cells from an organism, promote inflammation, and attack the pathogen’s cell membrane.

How Innate Immunity Works

When a pathogen breaches the body’s physical or chemical barriers, the innate immune system is activated. Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on immune cells, such as macrophages and dendritic cells, recognize specific molecules associated with pathogens, called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). This recognition triggers the release of cytokines, signaling molecules that recruit other immune cells to the site of infection and initiate an inflammatory response. Inflammation helps to contain the infection and promote tissue repair. The innate adaptive immunity response is quick, but it lacks the specificity and memory of the adaptive immune system.

What is Adaptive Immunity?

Adaptive immunity, also known as acquired immunity, is a more sophisticated and targeted defense system that develops over time as the body is exposed to different pathogens. Unlike innate immunity, adaptive immunity is highly specific, meaning that it can recognize and target specific antigens (molecules that trigger an immune response) associated with particular pathogens. It also has immunological memory, allowing it to mount a faster and stronger response upon subsequent encounters with the same pathogen. The collaboration between innate adaptive immunity is crucial for long-term protection.

Components of Adaptive Immunity

The key players in adaptive immunity are lymphocytes, specifically T cells and B cells.

- T Cells: These cells are responsible for cell-mediated immunity. There are two main types of T cells:

- Helper T Cells (CD4+ T cells): These cells help activate other immune cells, including B cells and cytotoxic T cells, by releasing cytokines.

- Cytotoxic T Cells (CD8+ T cells): These cells directly kill infected or cancerous cells that display foreign antigens on their surface.

- B Cells: These cells are responsible for antibody-mediated (humoral) immunity. When activated by an antigen, B cells differentiate into plasma cells, which produce antibodies.

How Adaptive Immunity Works

Adaptive immunity is activated when antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells, capture antigens and present them to T cells in the lymph nodes. This presentation activates T cells, which then proliferate and differentiate into effector cells (helper T cells or cytotoxic T cells). Helper T cells help activate B cells, which then differentiate into plasma cells and produce antibodies. Antibodies bind to antigens, neutralizing pathogens, marking them for destruction by phagocytes, or activating the complement system. This intricate process is a vital part of innate adaptive immunity.

The Role of Antibodies

Antibodies, also known as immunoglobulins, are Y-shaped proteins that bind to specific antigens. There are five main classes of antibodies: IgM, IgG, IgA, IgE, and IgD. Each class has a different function in the immune response. For example, IgG is the most abundant antibody in the blood and provides long-term protection against pathogens, while IgE is involved in allergic reactions and parasitic infections. The production of antibodies is a cornerstone of adaptive immunity and a key component in the overall efficacy of innate adaptive immunity.

The Interplay Between Innate and Adaptive Immunity

Innate and adaptive immunity are not independent systems; they work together in a coordinated and synergistic manner to provide comprehensive protection against pathogens. The innate immune system provides the initial, immediate response to infection, while the adaptive immune system provides a more specific and long-lasting response. The innate immune system also plays a crucial role in activating and shaping the adaptive immune response.

Examples of Innate and Adaptive Immunity Collaboration

- Dendritic cells, part of the innate immune system, capture antigens and present them to T cells, initiating the adaptive immune response.

- Cytokines produced by innate immune cells influence the differentiation of T cells and B cells, shaping the type of adaptive immune response that is generated.

- Antibodies produced by B cells enhance the ability of phagocytes to engulf and destroy pathogens, linking the adaptive and innate immune systems.

Immunological Memory

One of the key features of adaptive immunity is immunological memory. After the first encounter with a pathogen, the adaptive immune system generates memory T cells and memory B cells. These cells remain in the body for long periods of time and are able to mount a faster and stronger response upon subsequent encounters with the same pathogen. This is the basis of vaccination, which involves exposing the body to a weakened or inactive form of a pathogen to induce immunological memory and provide protection against future infection. The memory component is a critical distinction in innate adaptive immunity.

Dysregulation of Innate and Adaptive Immunity

Dysregulation of either the innate or adaptive immune system can lead to a variety of diseases.

- Autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, occur when the adaptive immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues.

- Immunodeficiency disorders, such as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) and HIV/AIDS, occur when the immune system is weakened or absent, making individuals more susceptible to infections.

- Allergies occur when the adaptive immune system overreacts to harmless substances, such as pollen or food.

- Chronic inflammatory diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), can result from dysregulation of both the innate and adaptive immune systems.

Conclusion

The immune system is a complex and dynamic network that protects us from a constant barrage of pathogens. Innate and adaptive immunity are two distinct but interconnected branches of the immune system that work together to provide comprehensive protection. Understanding the mechanisms and interplay between these two systems is crucial for developing new strategies to prevent and treat infectious diseases, autoimmune disorders, and other immune-related conditions. Further research into the intricacies of innate adaptive immunity promises to unlock new avenues for improving human health and well-being. The collaboration between innate adaptive immunity ensures long-term survival.

[See also: The Role of Cytokines in Immune Response]

[See also: Understanding Autoimmune Diseases]